This Federal Appeals Court's Ruling Put a Dent in Police Officers' 'Qualified Immunity' Defense

This piece originally appeared at , a project of the ╠Ūą─Vlogof Massachusetts.

A police officer is not immune from accountability after he points a gun at a non-threatening person, with his finger on the trigger and the safety off, and accidentally fires. So the First Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston last week, in a case that has far-reaching implications for public safety and police accountability.

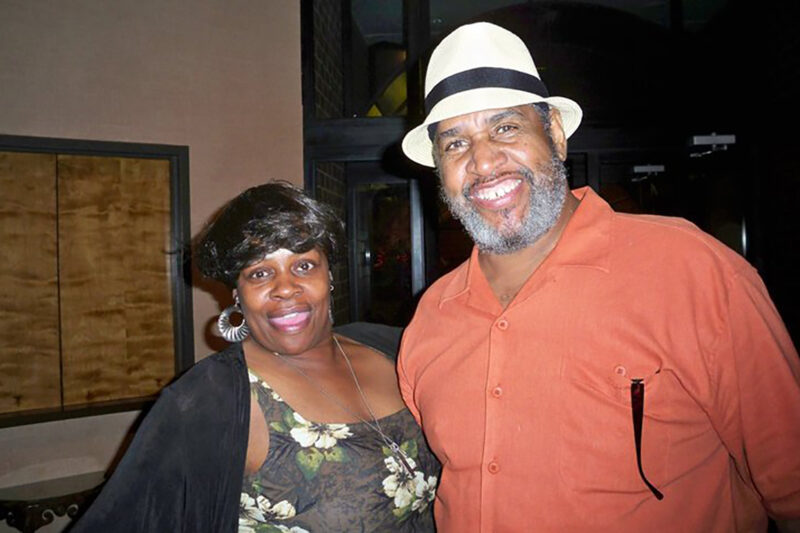

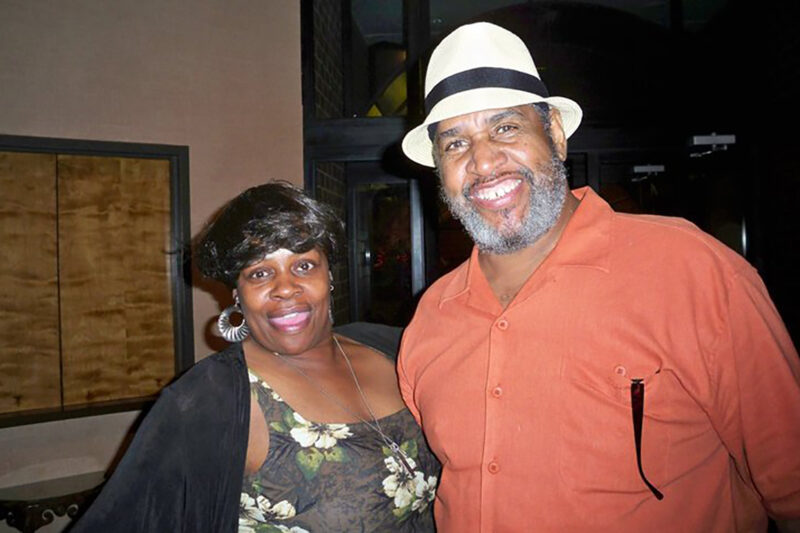

The stems from the 2011 Framingham, Massachusetts, of 68-year-old African-American grandfather Eurie Stamps. In the early morning hours of January 5, 2011, the Framingham SWAT team raided Mr. StampsŌĆÖ home with a search warrant because they suspected his stepson of selling drugs there. Mr. Stamps, whom officers knew would be in the home and posed no known threat, ended up dead.

When the Framingham SWAT team entered his home, Mr. Stamps complied with the officersŌĆÖ demands. He was lying on his stomach, his hands above his head, when officer Duncan accidentally fired his weapon, killing the beloved grandfather.

The case highlights the danger of using SWAT teams to conduct searches in routine drug cases ŌĆö a nationwide problem that disproportionately impacts Black and Brown Americans. In the deadly raid on Mr. StampsŌĆÖ home, the SWAT team entered unannounced in the middle of the night, threw a bomb into the home, and broke the door open with a battering ram before charging in, dressed like warriors. In these night-raids, when adrenaline is pumping and officers are decked out in combat gear and carrying powerful weaponry, tragic accidents can happen.

But even though Duncan fired accidentally, he isnŌĆÖt immune from Mr. StampsŌĆÖ familyŌĆÖs federal lawsuit, which alleges that the officerŌĆÖs conduct violated Mr. StampsŌĆÖ Fourth Amendment rights. The lawsuit seeks damages from both Officer Duncan and the Town of Framingham ŌĆö and thanks to last weekŌĆÖs ruling, it will move forward. A jury will now decide whether Paul DuncanŌĆÖs decisions to take his weapon off safety, place his finger on the trigger, and point it at a compliant Mr. Stamps violated StampsŌĆÖ Fourth Amendment rights.

As the ╠Ūą─Vlogof Massachusetts to the First Circuit,

"[S]hielding officers from liability for unreasonable actions that cause accidental deaths would acutely threaten the communities that are most frequently subject to militarized police raids and other police actions. Raids like the one that resulted in StampsŌĆÖs death increasingly bring military-style equipment and tactics into the homes of ordinary Americans. The risks endemic to these raids are borne especially by people of color, including Stamps himself, and it is these communities who will suffer the consequences [if the court agrees with the defendents]."

Thankfully, the First Circuit agreed. Last weekŌĆÖs ruling is a huge victory for the Stamps family, but it has implications that go far beyond the tragic circumstances of Mr. Eurie Stamps and his surviving loved ones. Thanks to this important decision, police officers in the First Circuit ŌĆö an area encompassing the districts of Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Puerto Rico, and Rhode Island ŌĆö cannot recklessly point their weapons at nonthreatening people and then claim immunity after they kill them, even if the killing is accidental.

Unfortunately, the ruling stands out. Decades of has made it increasingly difficult for people to hold police officers and departments accountable for actions that imperil public safety and endanger human life. ThatŌĆÖs because of the courtsŌĆÖ expansion of a legal doctrine called ŌĆ£qualified immunity,ŌĆØ which holds that police officers cannot be punished ŌĆö either in criminal courts or in civil litigation ŌĆö when they kill or injure someone, as long as the police officer didnŌĆÖt intentionally violate ŌĆ£clearly established law.ŌĆØ

As ╠Ūą─Vlogof Massachusetts legal director Matthew Segal said after reading it, the First Circuit ruling will help which gives law enforcement agencies far too much leeway to violate civil rights and liberties. ŌĆ£This is a landmark decision,ŌĆØ Segal said. ŌĆ£It confirms that, when police officers needlessly put members of the public at risk, the lives of those civilians matter. Victims of undue police violence deserve constitutional protection, and this opinion says that they have it.ŌĆØ

And as anyone whoŌĆÖs paid attention over the last few years knows, the ruling is likely to have a greater impact for communities of color, who are overrepresented at every stage of the criminal punishment system, from arrest to use of force to prosecution to incarceration to sentencing. ╠Ūą─Vlogof MassachusettsŌĆÖ Racial Justice Program director Rahsaan Hall put it like this: ŌĆ£DuncanŌĆÖs actions are symptomatic of a larger problem in policing. The way in which the police engage communities of color reveals bias and a general lack of empathy, which can oftentimes have deadly results. The reason activists take to the streets declaring ŌĆśBlack Lives MatterŌĆÖ is because of cases like this.ŌĆØ

Thanks to the First Circuit and the courageous Stamps family, police officers are now put on notice: You canŌĆÖt recklessly endanger someoneŌĆÖs life, kill them, and then claim you cannot be held accountable for your actions. When people are following police instructions and police shoot them dead, their lives matter, meaning our system must hold those officers and departments accountable.